His Blood is Bibline: Scripture in the Life and Work of John Bunyan (Reformation Today)

This draft paper was delivered at the Anchored Conference 2024, organised by Reformation Today. You can find an audio recording of it being delivered below.

The title of my paper is a reference to a famous comment that Charles Spurgeon, the leading Baptist preacher and pastor of the 19th Century, made about John Bunyan. In a sermon on 25 June 1882, Spurgeon was reflecting on the value and worth of Scripture, much like we have done together today at Anchored, and he gave his hearers the following exhortation:

“Oh, that you and I might get into the very heart of the Word of God, and get that Word into ourselves! As I have seen the silkworm eat into the leaf, and consume it, so ought we to do with the Word of the Lord—not crawl over its surface, but eat right into it till we have taken it into our inmost parts. It is idle merely to let the eye glance over the words, or to recollect the poetical expressions, or the historic facts; but it is blessed to eat into the very soul of the Bible until, at last, you come to talk in Scriptural language, and your very style is fashioned upon Scripture models, and, what is better still, your spirit is flavored with the words of the Lord.

I would quote John Bunyan as an instance of what I mean. Read anything of his, and you will see that it is almost like you are reading the Bible itself. He had read it till his very soul was saturated with Scripture; and, though his writings are charmingly full of poetry, yet he cannot give us his Pilgrim’s Progress—that sweetest of all prose poems — without continually making us feel and say, “Why, this man is a living Bible!” Prick him anywhere—his blood is Bibline, the very essence of the Bible flows from him. He cannot speak without quoting a text, for his very soul is full of the Word of God. I commend his example to you, beloved.”[1]

It is clear that Spurgeon saw something in the life and writings of John Bunyan that suggested that he had a particularly close relationship with and appreciation for this doctrine of Scripture. And as I have investigated this subject in preparation for this paper, reading Bunyan himself and a variety of secondary sources, I have found that that is certainly be the case. Spurgeon unsurprisingly was absolutely right. Bunyan is a brilliant example of a Baptist who embodied the doctrine that we have been considering together as part of this day. And that was the big idea for this final session, that we would look at how this particular doctrine, being that of Scripture, comes to life in the life and ministry of one of our important Baptist forebearers from history.

This paper will consider the centrality of the doctrine of Scripture for John Bunyan by considering: (1) how his interactions with Scripture shaped his overall life; and (2) how his views on Scripture can be seen in his works (systematics, hermeneutical, and some of the allegories he uses for Scriputre).

Scripture in Bunyan’s Life

How did John Bunyan manage to get the Bible into his very blood? How might we undergo a similar blood transfusion today? By reflecting on Bunyan’s life, I think we see that he absorbed the Bible into his blood in the same way that we all absorb oxygen into ours. That is, Bunyan breathed it in. The reason that Bunyan ended up with Bible in is blood, was that day by day, year by year, he breathed its air into his spiritual lungs. Indeed, so important was his relationship with Scripture, that some Bunyan scholars even propose Bible-reading to be the central theme of Bunyan’s two greatest works: his greatest allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress, and autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners. [2]

It is often pointed out how much these works have in common. Both are biographical. Pilgrim’s Progressnarrates the fictional life of Christian, and Grace Abounding the historical life of Bunyan. However, they also share another feature in common, in that they both describe how these two individuals, Christian and Bunyan, interact with the same book. If you know Pilgrim’s Progress, you will remember it begins with that famous scene: [READ]. The rest of the work goes on to describe Christian ongoing interactions with that book in his hand: how it causes him to leave the City of Destruction, lose his burden, and finally reach the Celestial City. Pilgrim’s Progress revolves around Christian’s relationship with the Bible. And you could argue that Grace Abounding, the narrative of Bunyan’s own life, is similar. For throughout, Bunyan tells the story of how he gradually grows and develops in his relationship with that very same book.

Just a reminder of Bunyan’s biography, for those who may need a refresher. He was born in 1628 in Elstow, just outside of Bedford, into a fairly poor family. His father, Thomas, was a brazier (or tinker) by trade. He was a metal worker who travelled from house to house, carrying his tools and anvil on his back, to mend household items like pots and pans. However, while Thomas Bunyan couldn’t write himself, he was eager to ensure his son learnt to do so.[3] As a result, John was sent to school until he was nine, when he had to start helping his father in the business to provide enough money for the family.[4] Nevertheless, this early exposure to reading and writing clearly took hold of young John, for even after he stopped school, he loved to read.

Reflecting back on his early life, he notes that this desire to read was entirely carnal at this stage. He comments, “Give me a ballad or a news book, “George on Horseback” or “Bevis of Southampton.” Give me some book that teaches curious arts, that tells of old fables, but for Scriptures I cared not.”[5] Bunyan grew up with little spiritual interest, and instead had a reputation for being the ringleader of a group of other young boys in Elstow that were quick to make mischief.

And yet, it is clear that Bunyan was profoundly thankful to his parents for making the sacrifices necessary in order to provide him with even this short period of education. He was later quick to ascribe their desire to do so to God, saying that it was the Lord that evidently put it into their hearts.[6] We can only imagine what the Christian world, indeed the entire literary world, would have lost had the author of the Pilgrim’s Progress never learnt to read and write. Indeed, Bunyan himself would later place such a priority on children learning to do so, that he wrote a book of poems for children that also included an alphabet for them to learn, and an explanation of how words on a page could be broken up into syllables. And explained that he did all of this for the express purpose that they might be able to read the Psalter or Bible.[7]

If his education was cut short so that he could work with his father, his time as a tinker was also cut short so that he could serve as a soldier. Bunyan was born at a time of great tension in England, and the storm finally broke as the Civil War began in 1642, when John was just 14. Bunyan was tall for his age, and so even before he turned 16, the age at which he was old enough to serve, he was prematurely conscripted into the Parliamentary army and stationed in a garrison at the nearby Newport Pagnell. While the three years he spent as a solider were eventful both on a national and personal level, there appears to be no spiritual change.[8] If before joining the army, Bunyan was known as a rebellious and licentious teenager around Elstow, this continued during these years. However, at the end of the Civil War, when he was decommissioned from the army, this all began to change. He seems to have struck up a relationship with a young woman during his time in Newport Pagnell, and was shortly thereafter married at the age of 20.

We know very little about Bunyan’s first wife. For example, in Grace Abounding, he doesn’t even tell us her name.[9] However, Bunyan does record two important details. Two facts that would begin to change his life for the better. First, he tells us that her deceased father was a godly man, and second, that he left her two books upon her death: The Plaine Man’s Path-way to Heaven and The Practice of Piety. Both were common spiritual writings at the time, and when she married Bunyan, they came with her into the marriage.[10] The previously wild and notoriously sinful Bunyan, had somehow ended up united to a godly wife, and she began to have a slow and steady impact on him. She quietly rebuked him for some of his sinful excess in language, and in response, he began to lead an outwardly moral life. He attended church and he stopped swearing. Indeed, he even began to read the Bible. Having been disinterested in it as a child and teenager, now as a young man, he later reflected that he began to take “great pleasure” in reading the historical parts, the stories in the Bible. Indeed, he started to become well known in the area for his knowledge of Scripture. And yet, he said that he had no taste for the epistles or doctrinal sections at this stage.[11] At this time, the Bible was something that we wanted to master, rather than something he would let master him.

Bunyan had undoubtedly become a better man, even if he was not yet a true Christian. However, this too would soon change as his relationship with Scripture continued to develop. One day he was walking through Bedford, and he overhead a conversation between a handful of housewives. Noticing that they were talking about the Bible, he was drawn to listen. However, he was struck by how they were not just speaking about Scripture, but with the very language of Scripture itself. He later remarked, “they spake with such pleasantness of Scripture language, and with such appearance of grace in all they said, that they were to me, as if they had found a new world”.[12] Those ladies had entered the world of the Bible, and now Bunyan wanted to enter that new world too. It was the Scripture saturated speech of those housewives that stoked Bunyan’s desire to start breathing the Bible into his own blood.

Bunyan wanted what they had, and so once again his relationship with the Bible took a step forward. First, he was disinterested in it, then he was intellectually stimulated by it. But now he was spiritually hungry for it. He later reflects in Grace Abounding, “The Bible was precious to me in those days. And now, me thought, I began to look into the Bible with new eyes, and read as I never did before; and especially the epistles of the apostle Paul were sweet and pleasant to me; and, indeed, I was then never out of the Bible, either by reading or meditation still crying out to God, that I might know the truth, and way to heaven and glory.”[13]

Bunyan had fallen in love with the Bible, and yet as he suggests there in his quotation, he still did not know the God of the Bible. If you are familiar with Bunyan’s story, or after this lecture take the time to read through Grace Abounding (his spiritual autobiography), you will realize that overhearing that conversation in Bedford, and beginning to really and truly read the Bible, started a long and slow process of conversion for Bunyan. He experienced what amounted to excruciating conviction of sin over the course of a number of years, repeatedly being cast into the depths of despair as he recognized his own unworthiness and utter sinfulness. And yet, each time, Bunyan explains how he manages to find release from the terror of Hell and dungeon of his own doubts, through his reading or recollecting of a particular promise in the Bible.[14] On one occasion, it was the truth of Hebrews 2:15, of how Christ partook in our human flesh and blood to “deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery.” On another, it was the reality that despite the ups and downs that Bunyan felt in life, Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8). It seems that during this season, Satan tried to cut this comfort off at the source, by tempting Bunyan to doubt the truthfulness of Scripture, for he tells us of times that he was tempted to think of it as all just a fable.[15] However, having had his eyes opened to this new world of the Bible, Bunyan would not shut them, and he gradually learned to wield this two-edged sword of the Spirit even against Satan devices. He grew in faith and assurance, and was drawn into the life and membership of the local Baptist Church in Bedford.

The pastor, Andrew Gifford, personally began to invest time and energy in mentoring Bunyan. Given his dramatic personal testimony, and growing skill in using the Scriptures, we are perhaps unsurprised that he was encouraged to share his story and speak from Scripture to others. He was asked to begin preaching in nearby villages as a lay preacher, all the while still working away as a tinker to support his growing family. And he started to gain a reputation for a being powerful and persuasive evangelist. He also began to write, his first book demonstrating just how great a grasp of the Bible he already had. For it was a 40,000-word polemical work against some common errors regarding the human nature of Christ which he had encountered in Quakerism.[16] Though he was still a tinker, Bunyan had started to make an impact in Bedfordshire. No longer wielding the sword of Scripture against his own doubts, he was now using it against opponents of the Gospel. Not only was he drawing comfort from the promises for himself, but he was now giving that same comfort to others as well, calling them to believe in the God of the Bible for themselves.

However, towards the end of 1660, at the age of 32, his life took a dramatic turn. In preceding years, non-conformists had come under increasing political pressure and persecution. Bunyan had experienced some of this himself already, facing severe opposition from local Anglican leaders over his preaching, and the Baptist church in Bedford had recently been thrown out of their building. Following the collapse of the Commonwealth and restoration of the monarchy, the pressure increased again. And on 12 November 1660, local constables burst into a secret gathering on an isolated farm, where Bunyan was preaching, and arrested him for doing so. The local magistrate had been watching Bunyan for a while and decided that enough was enough, issuing a warrant for his arrest and tracking him to the farm that day. Bunyan had been warned that he was likely to be caught there, but he insisted on going and preaching anyway. Which gives us a taste of his determination to continue this ministry of preaching Scripture no matter the personal cost.

It is perhaps helpful to reflect on just what was at stake for Bunyan in these days. He was a tinker by his profession, he was not a pastor at this time but was instead a lay preacher, albeit a very successful one. Further, he had many household pressures and responsibilities. He had four children, the oldest of whom was blind. His first wife had recently died, and his second wife Elizabeth was a young woman, who at that very moment was pregnant with their first child together. As such, Bunyan had many ‘good’ reasons not to go to prison. Preaching wasn’t his fulltime calling. His family were in great need. Throughout his imprisonment, it was made clear to him that he would be freed if he simply promised not to go preaching again. And yet, so strong was his conviction that he must speak of those things that he saw in Scripture, he refused to make that promise, no matter the cost.

And the cost for Bunyan was high. The shock of his arrest was so great, that his young wife went into premature labor upon hearing of it and they lost the baby.[17] And this was just the start of her suffering, for his family would continue to suffer much hardship and poverty for the duration of his stay in prison. And yet, Bunyan’s commitment to proclaiming the promises of the Bible did not weaken during these years. As he explained when he was eventually brought to trial, if they let him out of prison today, he would go preaching the Gospel tomorrow. And so, Bunyan was forced to remain in prison, and would stay there for the next twelve years of his life.

Bunyan’s opponents in Bedfordshire must have thought they had won a great victory, keeping the preaching tinker behind bars for all those years. And yet, Bunyan’s life in prison is a wonderful example of what Paul declared in 2 Timothy 2:8–9, “Remember Jesus Christ, risen from the dead, the offspring of David, as preached in my gospel, for which I am suffering, bound with chains as a criminal. But the word of God is not bound!” Like Paul, Bunyan may have been in prison, but the Bible’s work in and through Bunyan did not stop. Once again, his relationship with Scripture entered into a new phase. He himself would attest to this fact, explaining that this suffering allowed him to see something new in Scripture. He writes, “I never had in all my life so great an inlet into the word of God as now. Those Scriptures that I saw nothing in before are made in this place and state to shine upon me. Jesus Christ also was never more real and apparent than now; here I have seen him and felt him indeed.”

Those same twelve years that Bunyan would be locked behind prison doors, kept away from his church and all the opportunities for service that he previously had, became the most fruitful and impactful years of his life. As one commentator puts it, “The bars that bound John Bunyan’s body were as wings to his soul. Never does his spirit soar heavenward with greater freedom, nowhere is the music that falls from his uplifted soul sweeter.”[18] Indeed, had Bunyan not been put in prison and so providentially given the space and experienced the suffering he needed to write his most famous works, it is questionable whether we would even know his name today. As a tinker, Bunyan shaped metal with his tools on the little anvil he carried around. But as a Christian, he himself was shaped by Scripture on this anvil of his suffering.

During the first six years of his imprisonment he penned several profitable works, including one on prayer and another on the Christian life.[19] Amusingly, he even kept preaching, to his fellow prisoners around him, and he would then write up and publish those sermons too.[20] And near the end of those first six years, he penned a spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners.[21] And then, at the end of those first six years his pen fell silent. And for the next six years in prison, he did not publish a single work. For he was working on something truly special. It seems that while writing up a sermon on 1 Corinthians 9:24, which he called The Heavenly Footman: A Description of the Man that Gets to Heaven, an idea flashed into his mind for another work, it would be an allegory that would describe a man’s journey to glory. It would be called The Pilgrim’s Progress. While it was published after Bunyan was released from prison, it was written during his time in jail. Indeed, the opening line we read earlier even alludes to that, for that den in the wilderness, where he said he had the dream, was simply an imaginative way of describing Bedford prison. It would become one of the best-selling books in history, indeed by the middle of the 20th century, the only book that had sold more copies than Pilgrim’s Progress was the Bible itself, the book that Bunyan loved above all others.

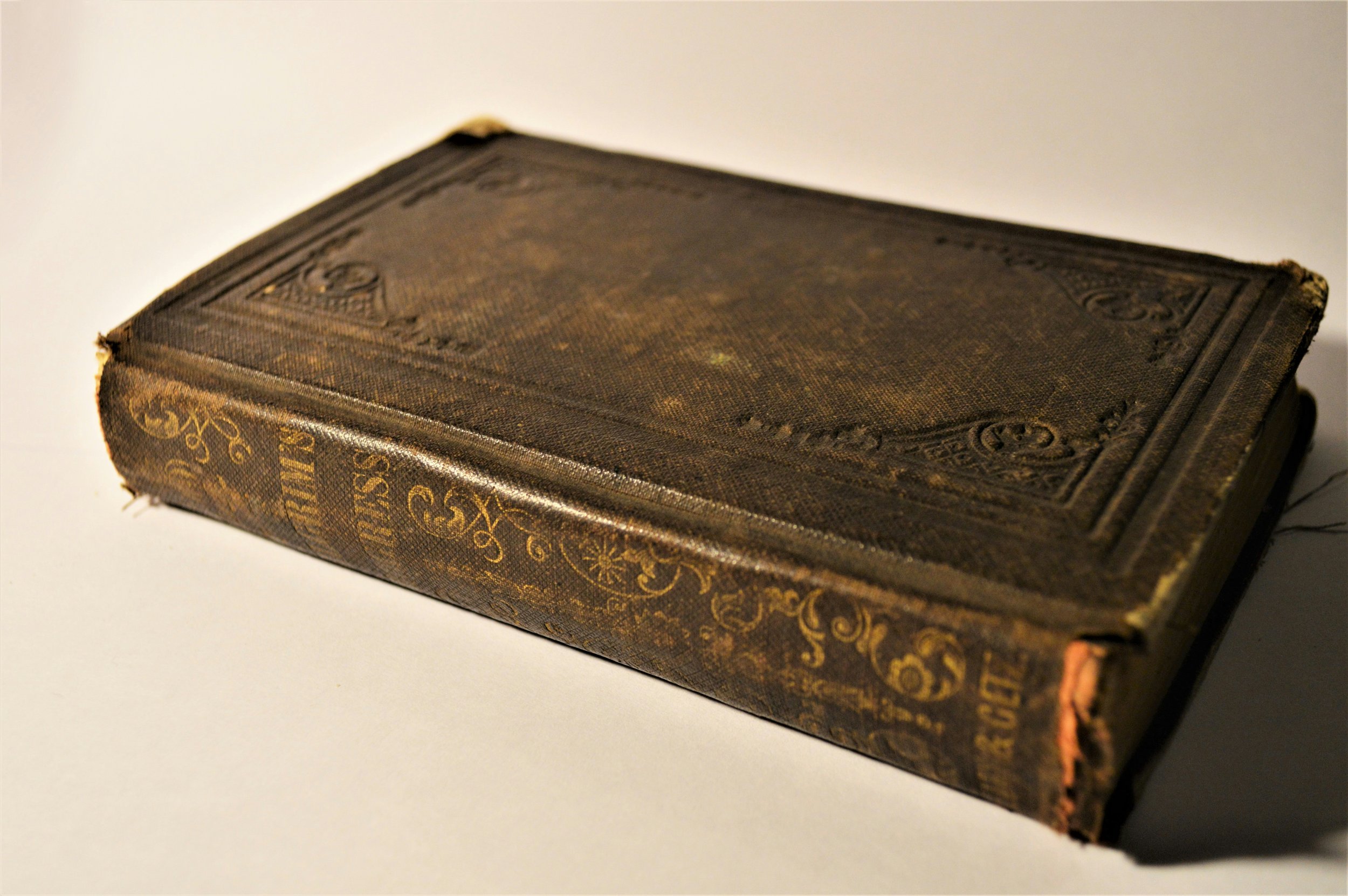

After his release, Bunyan would go on to write many other works, and kept preaching and ministering around both Bedford and in London itself. However, he famously said, that as he wrote all these works, he only ever had two books beside him: the Bible and a concordance of the Bible.[22] Bunyan remained thoroughly bibline from beginning to end. As he would later put it, “I depend upon the saying of no man. I [find what I write] among the Scriptures of truth, among the sayings of God.”[23] And so in the 19th Century, when a monument was finally placed on his grave in London’s Bunhill fields, it was fitting that Bunyan was sculptured according to that opening scene of Pilgrim’s Progress, as a man with a book in his hand. For it was Scripture that had most shaped his life. Just as Spurgeon had put it, Bunyan had managed to breath the Bible into his very blood.

Scripture in Bunyan’s Works

Given that Bunyan’s life was so entirely shaped by Scripture, it is unsurprising that it was also an important theme of many of his writings. And yet, interestingly, he never produced a treatise that dealt directly with the topic. Bunyan certainly agreed with the systematic statements we considered earlier on the doctrine of Scripture, as seen in the Second London Confession. For example, on one occasion he emphasised the authority of Scripture, or the divine vocalitywe were hearing about, writing, “Thou must give more credit to one syllable of the written Word of the Gospel than thou must give to all the Saints and Angels in Heaven and Earth.”[24] Similarly, in another place, he cites 2 Timothy 3:16 in relation to the inspiration and sufficiency of Scripture. He would say, “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God... able to give a man perfect instruction into any of the things of God necessary to faith and godliness”.[25] Bunyan was thoroughly orthodox in his overall doctrine of Scripture. And yet, he never set this down in a single work. Scripture was always present in his works, but it was rarely the direct object of his attention. Scripture gave him the light he needed to see everything else by, but he never took the time to gaze directly into that light itself.

Similarly, Bunyan’s approach to interpreting Scripture is never directly addressed by any one work. However, his hermeneutical perspective is evidenced in everything he wrote and does differ from how we may naturally approach Scripture as modern evangelicals today. Back in 1927, one commentator pointed out that when using Scripture, Bunyan “is not afraid to use it in fragments torn from the context, and with a freedom that would appall modern exegetes.”[26]And if that was true 100 years ago, how much more true today is it today? It has to be admitted that Bunyan often fails to follow the historical-grammatical method, and is quick to allegorize Scripture in a way that most of us would be uncomfortable with. For example, he takes dietary laws in Deuteronomy to speak of the different spiritual states of people, with animals chewing the cud to mean those people who read God’s Word, and having a divided hoof, to mean those who turn from sin and walk in obedience to God.[27] While works like Pilgrim’s Progress and the Holy War are his most famous and developed allegories, and allegorical approach to Scripture can be seen in many of his other works. Indeed, in the preface of Pilgrim’s Progress he even defends his use of allegory in that work by referring to how Scripture often uses it as well.[28]

This allegorical approach to interpretation enabled Bunyan to have an emphatically spiritual and highly experiential style when preaching and writing. If you remember, in Bunyan’s own life, there was a period in his youth when he enjoyed reading historical parts of the Bible, like the Old Testament narrative, but had no taste for the doctrinal elements, such as the epistles. And it could perhaps be argued that he went onto overcompensate for this error, later turning every text into doctrinal treatise. Transforming every story into epistle like doctrinal clarity. His exposition of Genesis 1–10 is a good example of this, [29] with the story of Noah and the flood being developed into a rather elaborate allegory that he saw as typologically speaking of the state of the church and the salvation of the Gentiles in his day. We might wonder at this today. However, in this Bunyan was always in step with other interpreters of his generation, for such an approach was common among 17th Century writers. And if they were sometimes too imaginative, we could equally perhaps be described as too rigid in our hesitancy to consider the typological connections that have been placed throughout Scripture by its divine author. Indeed, we could be accused of committing the worst form of chronological snobbery, suggesting that pre-enlightenment preachers did not know how to read their Bibles as well as we do today. It should be clear that we have much we can learn from men like Bunyan. Yes, we should avoid their excesses, but we must not neglect their value.

Further, we should not forget that on the spectrum of his time, Bunyan was also fairly balanced. For he plotted a middle course between the pure reason of Latitudinarianism, and the radical spiritualization of the Quakers.[30] Bunyan insisted that the story of our lives must be read within the story of the Bible, and that it has real doctrinal implications for us today. And yet, on the other hand, he held that there is more to learn from a passage than may first meet our eye, and so we must approach a text not only through reason, but also in faith.[31]

Given Bunyan’s flare for allegory, it is unsurprising that we can perhaps learn about his view of Scripture most easily by considering the allegories that he uses for it in his works.[32] Again and again, Bunyan would depict the Bible in different ways, each bringing out a specific characteristic or use of Scripture. And as we close, I want to highlight four of the most famous ways he depicts Scripture in his allegorical writings. What did Bunyan understand the Bible to be? In four words, he saw Scripture as: (1) a book, (2) a key, (3) a sword, and (4) a mirror.

Firstly, a Book. We have seen that that is how the Bible is described at the beginning of Pilgrim’s Progress. In Bunyan’s dream he saw a man standing with a great burden on his back, and a book in his hand. And yet, it is important for us not to miss the connection between those two things, between that burden and that book. [READ] Later, through a conversation with Worldly Wiseman, Bunyan makes the connection even clearer, as he has Christian explain that he obtained this burden on his back by reading the book in his hand.[33] Before the Bible brings Christian comfort in the story, it first is an instrument of condemnation, a cause for bringing him under great conviction. As we shall see, Scripture will show Christian his Savior, but first of all it must show him his sin. It is that book that brings him to the point that he cries out that question of the Philippian jailor – what must I do to be saved? A question that that same book is alone able to answer. That is how the Bible first began to function in Bunyan’s own life. He would later reflect on those days and say that when first reading the Bible, he could draw no comfort from it and could only see his own destruction. He explains, “The people of God would tell me of the promises. They might as well have told me to reach the sun with my finger.”[34]That is where the Bible began for Bunyan, as it does for all of us, just as Jeremy reminded us of this morning. The first thing that the Bible does is to make us wise unto salvation. It is firstly a book of God’s law, that must first leave us burdened by our guilt, for it is only by doing so that it will leads us to the cross, where we can lay that great burden down.

Second, the Bible is also depicted as a key in Bunyan’s writings. This is perhaps the most famous depiction, in a scene you are probably familiar with, when Pilgrim is imprisoned in the dungeon of Doubting Castle. As he sisters in that dungeon, Christian finds himself being dragged down further and further into despair, until through prayer he suddenly recalls that he has a key in his pocket, a key that can open any lock in Doubting Castle, a key that he calls Promise. When you read through Grace Abounding, it is clear that this part of Pilgrim’s Progress is an incredibly personal one for Bunyan. For long before he was thrown into a physical dungeon for preaching God’s promises, he learnt how to escape from his spiritual dungeons by using those very same promises. As we heard earlier, when he was cast again and again into doubt and despair, he repeatedly righted himself by clinging onto the promises that God makes in Scripture. As he said on one occasion, “The Scriptures were now also wonderful things unto me. I saw that the truth and verity of them were the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven... Now I began to consider with myself that God had a bigger mouth to speak with than I had a heart to conceive with.”[35] God's promises are bigger than our capacity to understand them. Long before he penned one of his most famous scenes, Bunyan himself learned how to escape from Doubting Castle using the very same key.

Thirdly, echoing the imagery that Paul uses for Scripture in Ephesians 5, Bunyan also depicted Scripture as a sword. For in his great battle with Apollyon, Christian defeats the Devil by wielding verses from both the Old and the New Testament, and then delivers the death blow using a two-edged sword.[36] Similarly, in the second part of Pilgrim’s Progress, Mr Valiant-for-truth wields a Jerusalem blade, which he says can divide between flesh and bones, soul and spirit, which he uses not only against the attacks of Satan, but his own indwelling sin.[37] And at the end of the second part of Pilgrim’s Progress, Bunyan has Mr Valiant-for-truth leave it on the side of the river, before he crosses over into the Celestial City. And he leaves it there for all those who come after him, to take up and wield it, if only they have the courage and skill to do so.[38] Bunyan could speak of this in his own life, and explained in his book, Acceptable Sacrifice, that the work of God’s Word “is as the roaring of a lion, as the piercing of a sword, as a burning fire in the bones, as thunder, and as a hammer that dashes all to pieces.”[39]

Finally, Bunyan depicts Scripture as a mirror, or using the term for it at the time, a looking glass.[40] This was a common image for the Bible among 16th and 17th Century writers. For example, this was one of Calvin’s favorite ways to speak about Scripture. As we have seen, like a mirror, the Bible allows us to see ourselves as we truly are, as guilty sinners before a holy God. That was how the metaphor was usually used. And yet, in his description of the Bible as a looking glass, Bunyan interestingly adds something else. Near the end of the second part of Pilgrim’s Progress, we encounter a great mirror in the Shepherd’s Palace. It is a special mirror, for while it shows you a true reflection of yourself if you look at it one way, you need only turn it slightly and suddenly you see an altogether more glorious sight. For as Jeremy highlighted this morning, Scripture not only provides a true picture of ourselves, but it also provides a perfect picture of Jesus Christ.

Listen to how Bunyan puts it in his allegory: [READ]. Bunyan is clear, that Scripture not only allows us to see ourselves, but it also allows us to look upon Jesus, to watch him both suffer in our stead, and reign as our head. And we have already heard how this was Bunyan’s own testimony, for while he sat in that prison cell, staring into the Scriptures, he was able to see Jesus himself set before him in the mirror of his Word.

Remember what he said at he sat in prison, “I never had in all my life so great an inlet into the word of God as now. Those Scriptures that I saw nothing in before are made in this place and state to shine upon me. Jesus Christ also was never more real and apparent than now; here I have seen him and felt him indeed.”

Conclusion

Such was the bibline blood of John Bunyan. Scripture shaped his entire life, and it provided the basis for, and permeated through all his works. As a result, we can be unsurprised that he has remained so popular across the centuries, for this was a servant who was saturated in the timeless truth of Scripture.

We have already heard how highly Charles Spurgeon rated Bunyan. And you don’t have to read about Bunyan long to realize that he was not alone in his admiration. For example, the great puritan theologian, John Owen, was both a contemporary of Bunyan and also a vocal supporter. Owen had this tinker preacher to come to preach in Owen’s pulpit for his congregation in London. And the famous story is told of a conversation between Owen and the newly restored monarch, Charles II. The King asked Owen how, with all his great learn, he could go to hear the prattling of a common tinker, Owen the great scholar and think replied, “Had I the tinker’s abilities (to preach)… I would most gladly relinquish all my learning.’

Charles Spurgeon, perhaps the greatest preacher that the English speaking world has every heard, highlighted the value of Bunyan. John Owen, perhaps the greatest theologian that the English speaking world had ever seen, saw the same. Given both of these men could not speak highly enough of John Bunyan, we should surely think highly of him too.

However, as we close, I want to char a wonderful encouragement for those of us who feel like we can’t quite its reach the heights that he did. It can be tempting to idolise Bunyan, and become discouraged in ourselves. And yet, Bunyan himself confesses that he had both good days and bad, that sometimes he saw much, and at other times he saw very little. For example, on one occasion he declares: “I have sometimes seen more in a line of the Bible than I could well tell how to stand under, and yet at another time the whole Bible has been to me as dry as a stick; or rather, my heart hath been so dead and dry unto it, that I could not conceive the least drachm of refreshment, though I have looked it all over.”[41]

This is surely an encouragement for all of us who have yet to bring the Bible into our blood, to keep staring into Scripture, keeping looking for our Lord in the mirror of his Word, that like Bunyan, and like those housewives of Bedford that inspired him, we too may not only speak about, but speak with, even sound like Scripture.

[Footnotes to be added]